The misadventures of a junior Data Analyst

In this article, we’d like to highlight how getting relevant data from your system is not the end of the journey for a complete Data Analysis. Once you have your data, what do you do with it? How do you organize it and present it in a meaningful way, so that you and other people can gain some actual value from it?

A part of the Data Science process, Data Visualization is a vital part of data analysis but it is, unfortunately, often overlooked and underestimated. Even if the data we are representing is correct, the way we choose to build a graph or chart impacts the way data is perceived. Favoring one representation over the other can also lead the observer to one conclusion that may not be totally correct.

As an example, today we’d like to follow the work of an inexperienced data analyst: Bob.

Introducing Bob

Bob works for a made-up hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

The hospital has collected data on its patients and the reasons for admission (encounters) and medical treatment (procedures) they received at the Hospital.

Task: Bob is given the dataset*, and he is tasked with presenting this data to the management board.

His main objectives are:

-

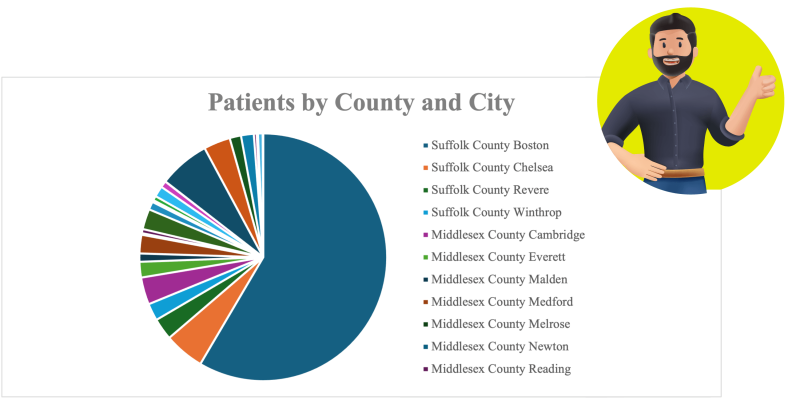

Give an overview of the patients’ age, gender and County/City

-

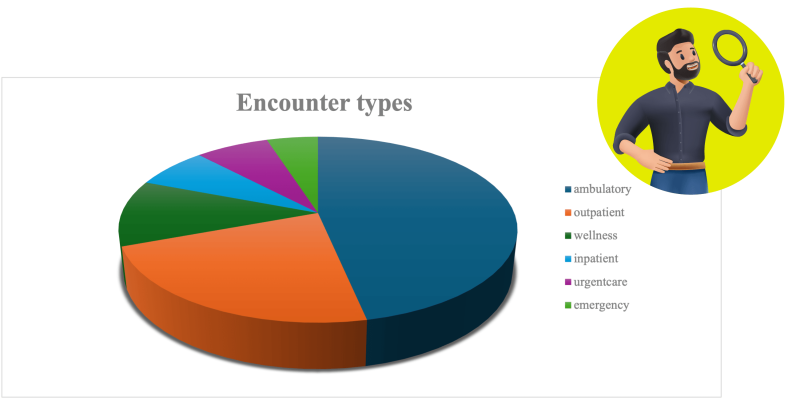

Analyze the type of encounters

-

Analyze the number of procedures done in 2020 to highlight any downwards trend

-

See if there is any evidence to support the investment in an Asthma Program at the Hospital

*The dataset is available here (Hospital Patients Records) and all analysis and visualizations have been done using excel, as this is a tool generally available to everyone.

Bob’s Analysis

Data Analysis – Patients’ data

Let’s see what Bob does and how he chooses to present the data.

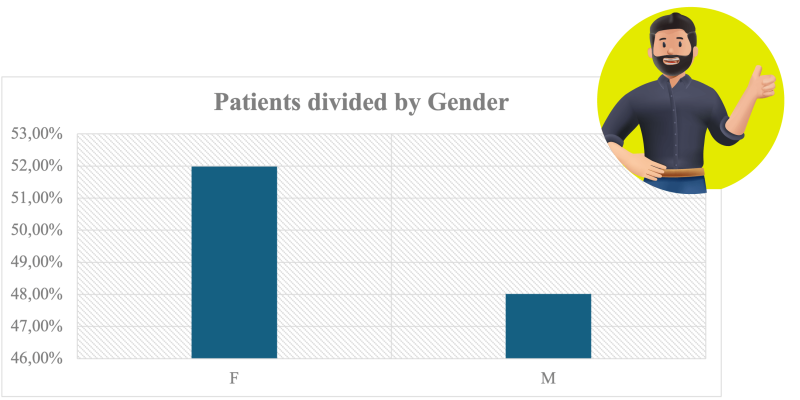

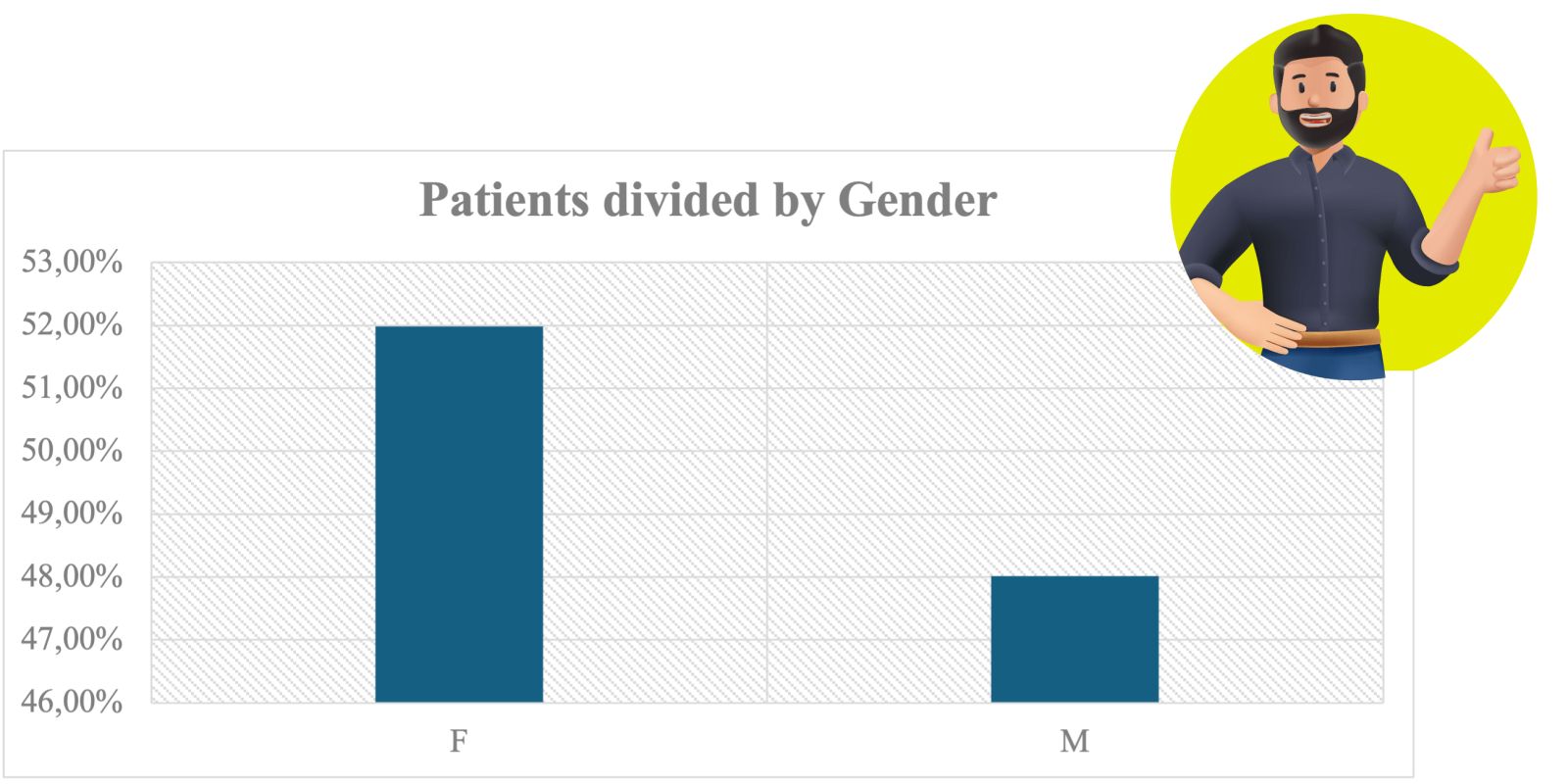

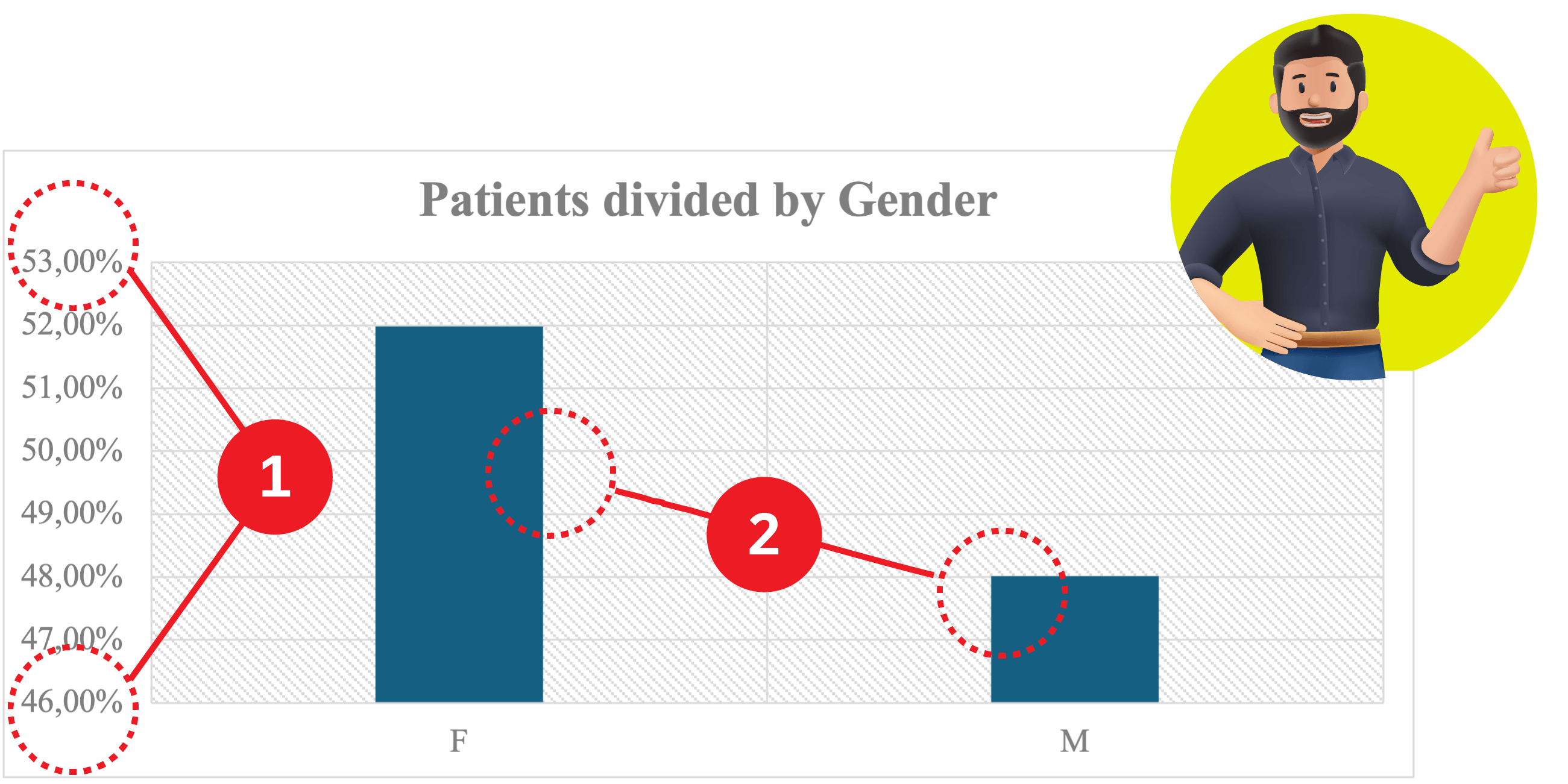

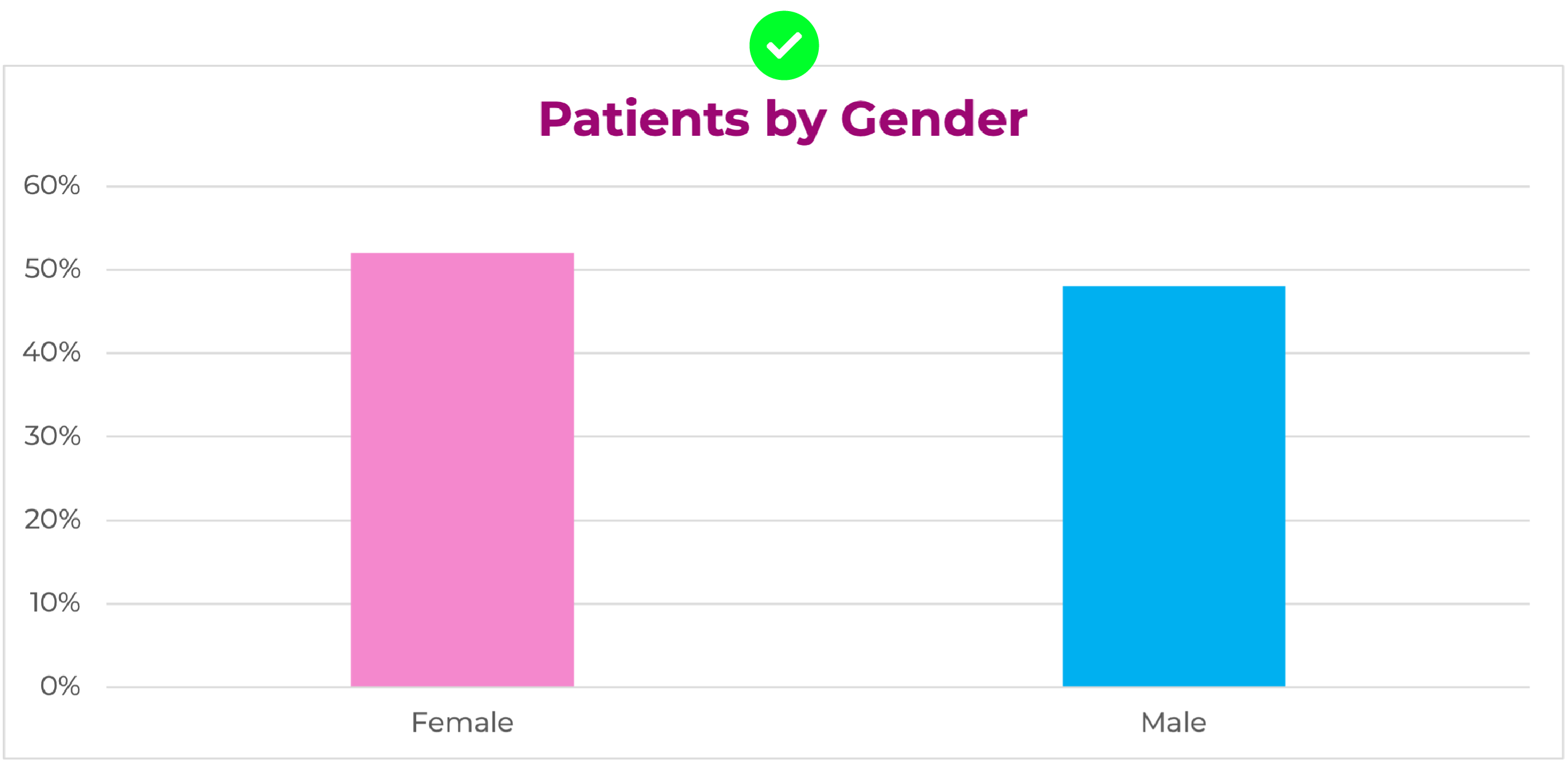

Patients divided by gender

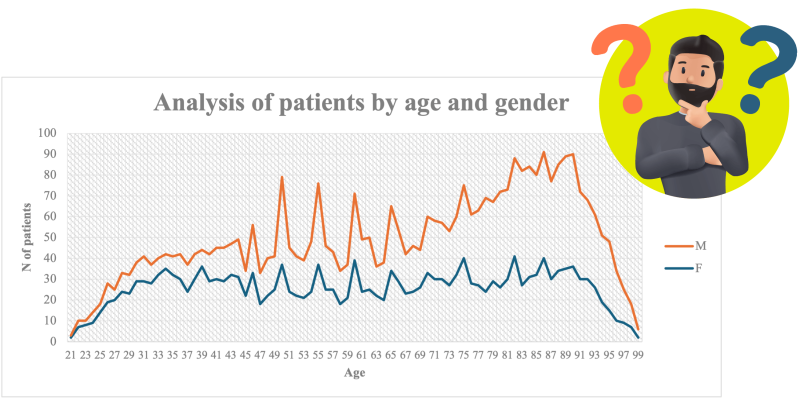

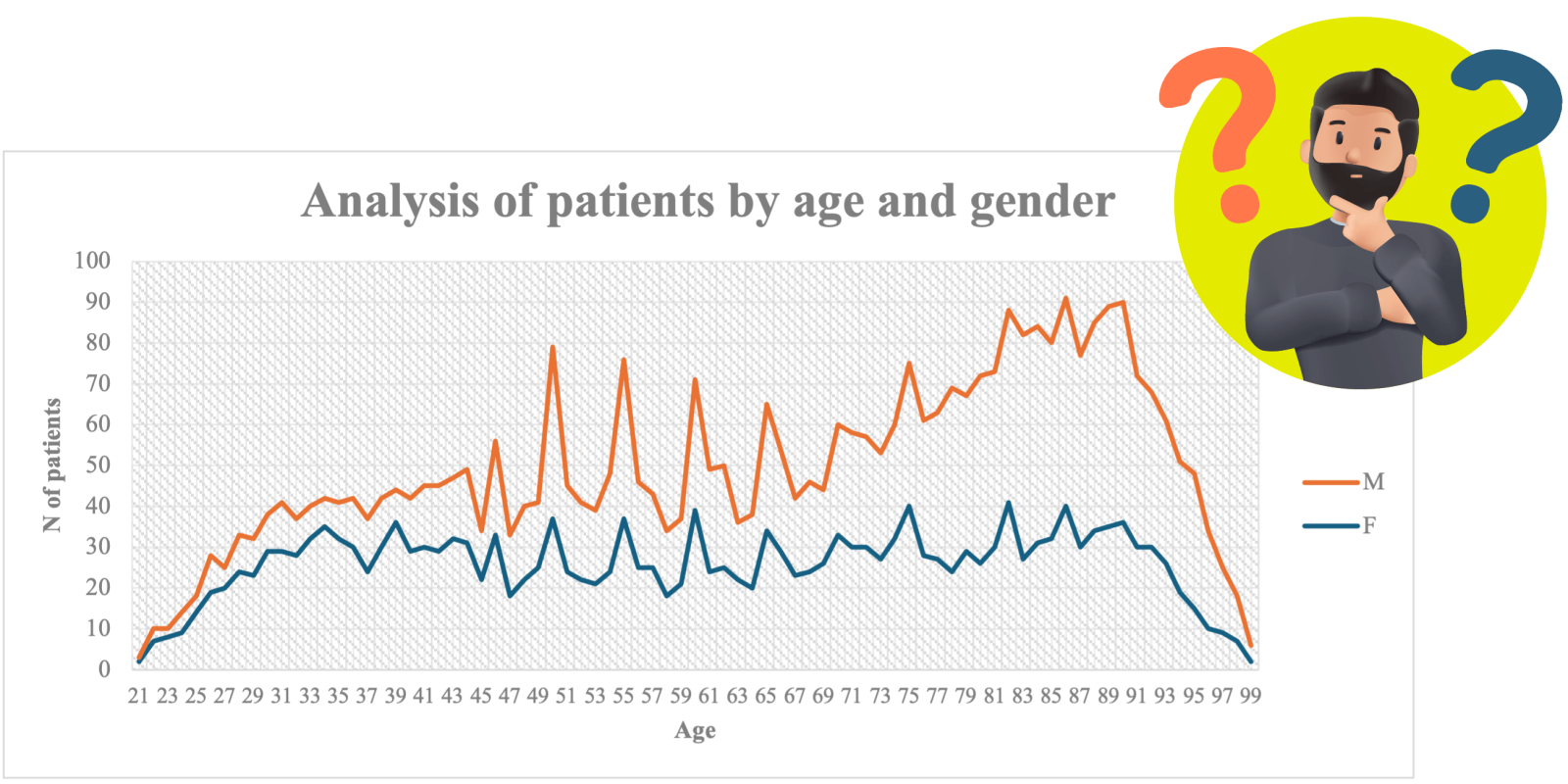

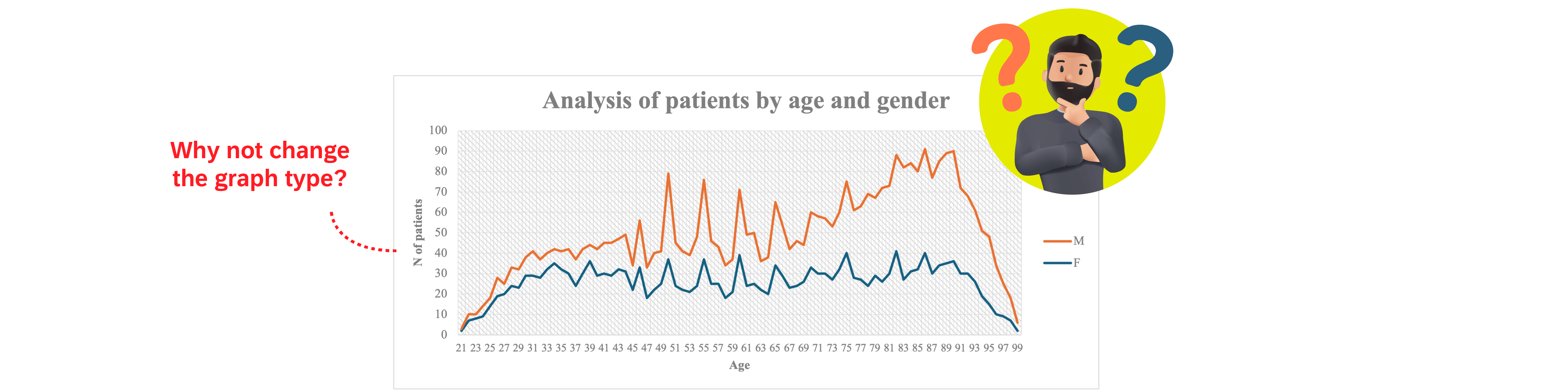

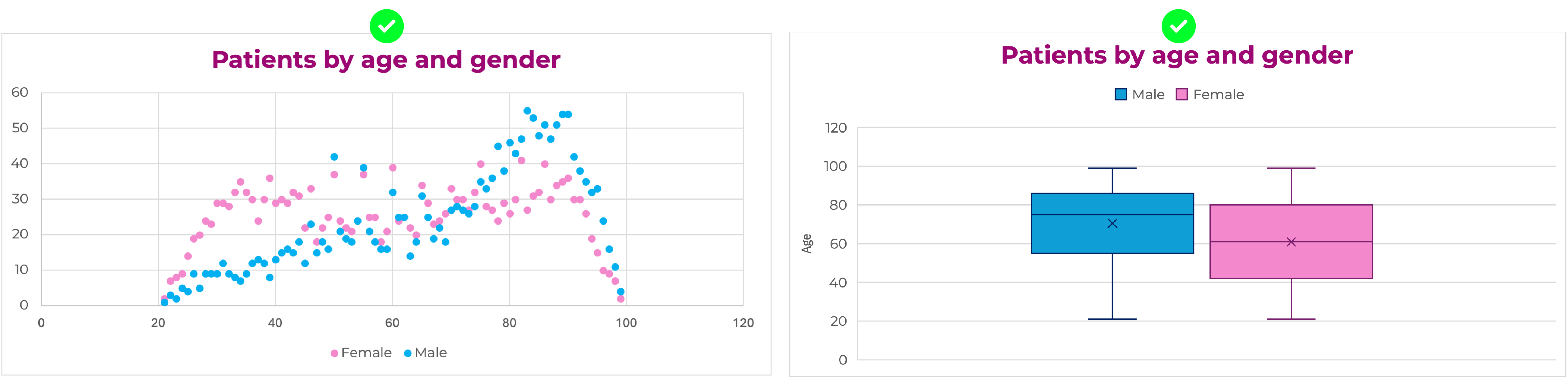

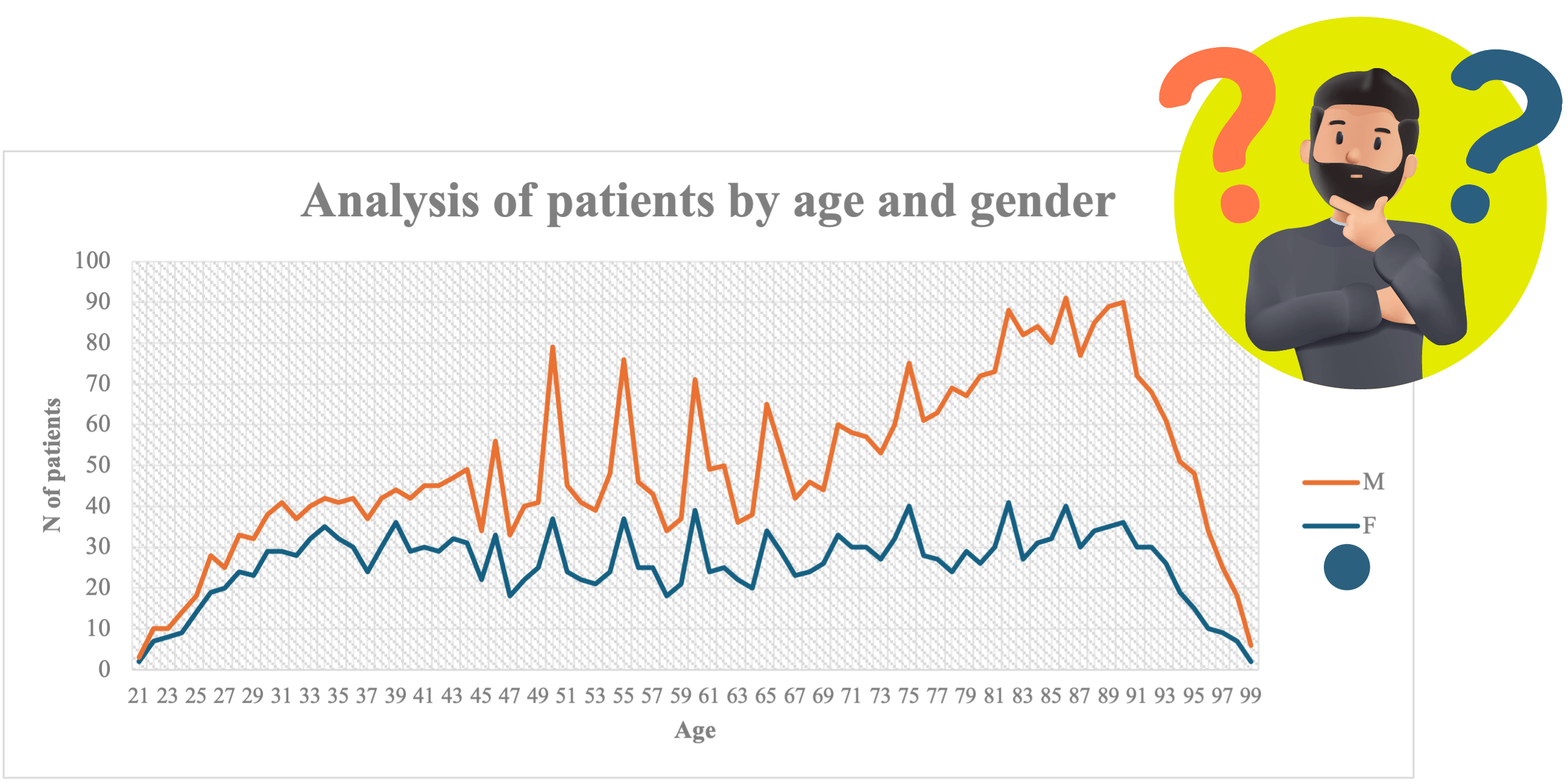

Patients divided by age and gender

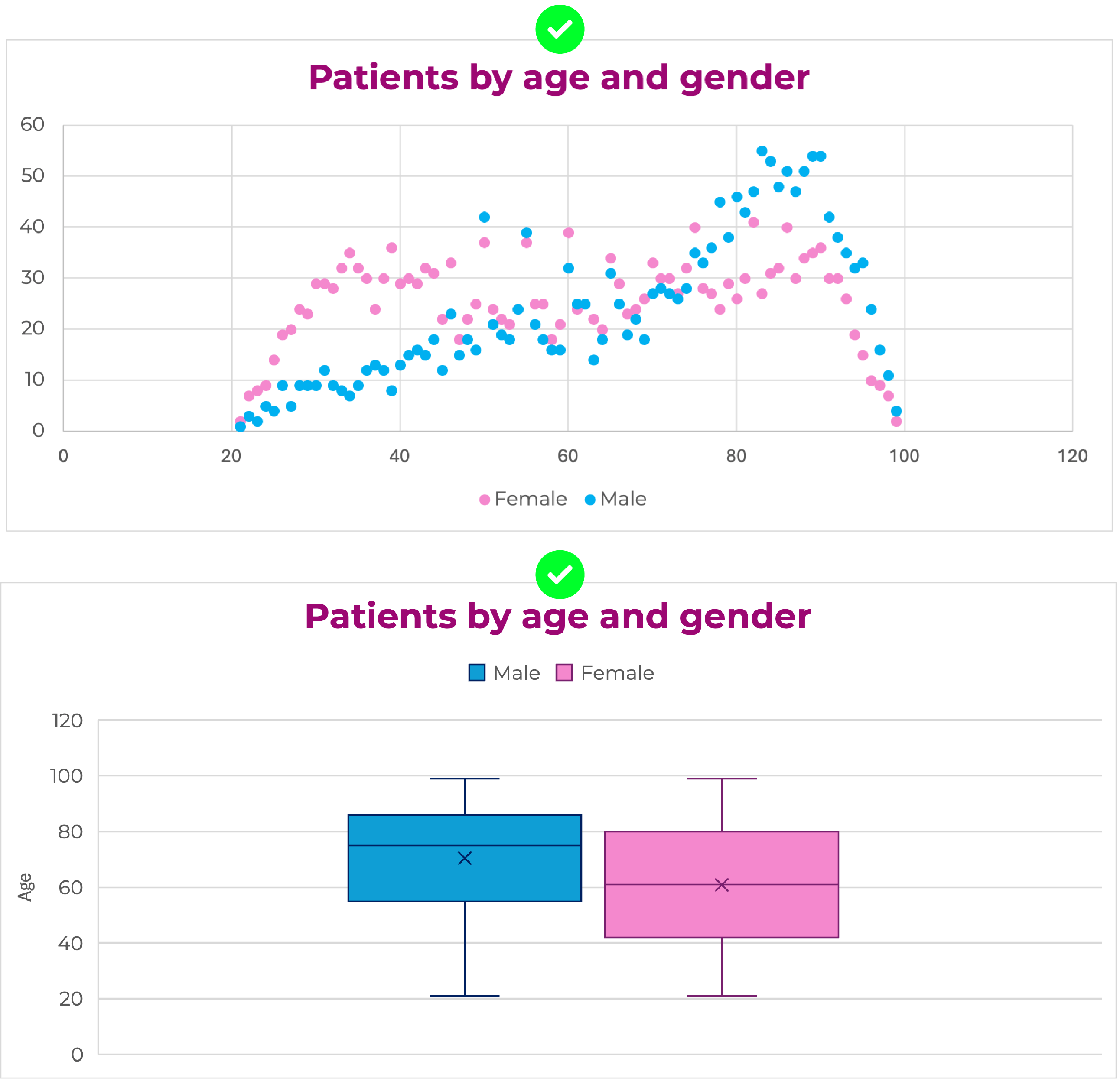

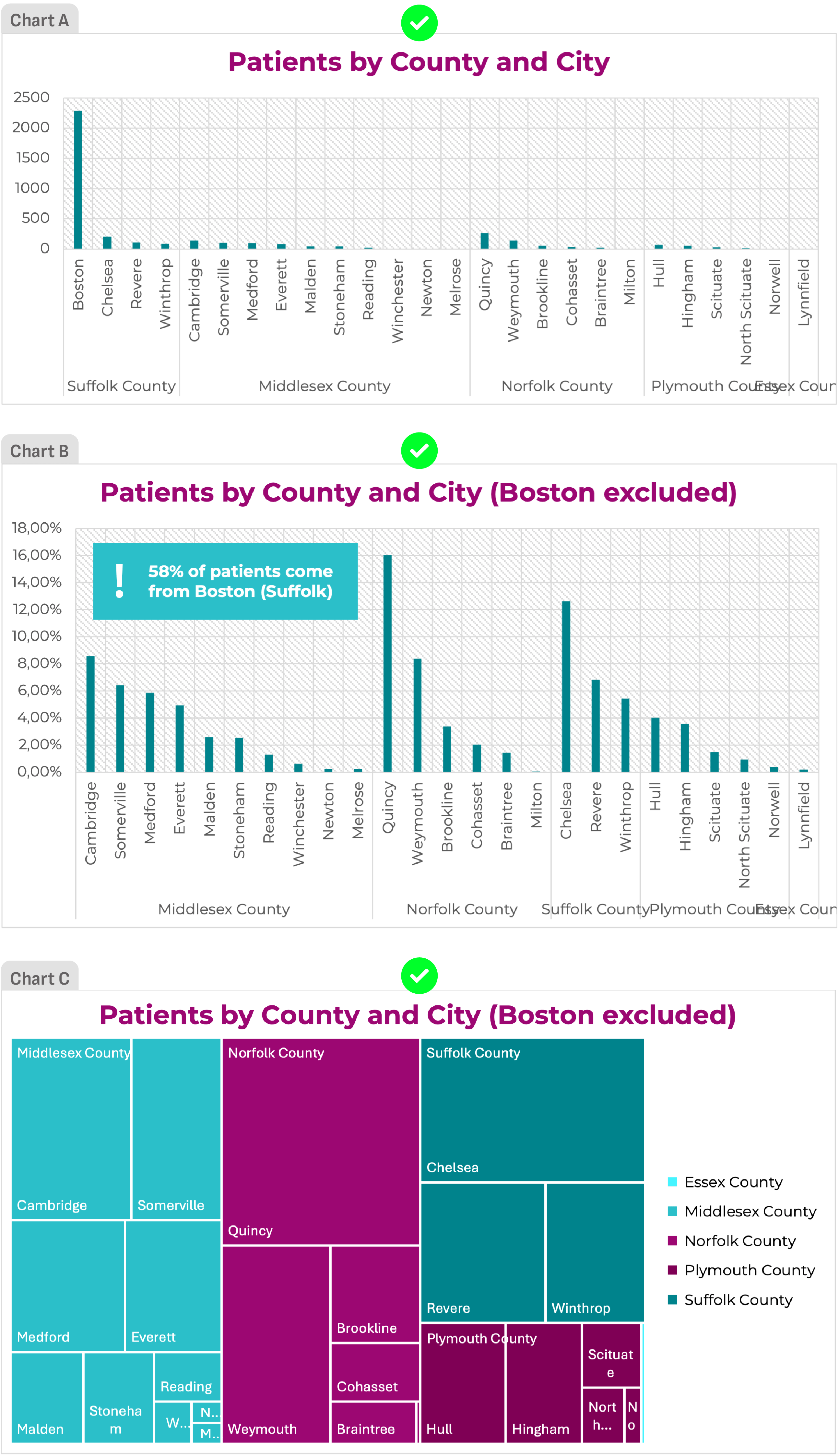

Patients divided by country and city

Bob’s Analysis

Data Analysis – Encounters and procedures

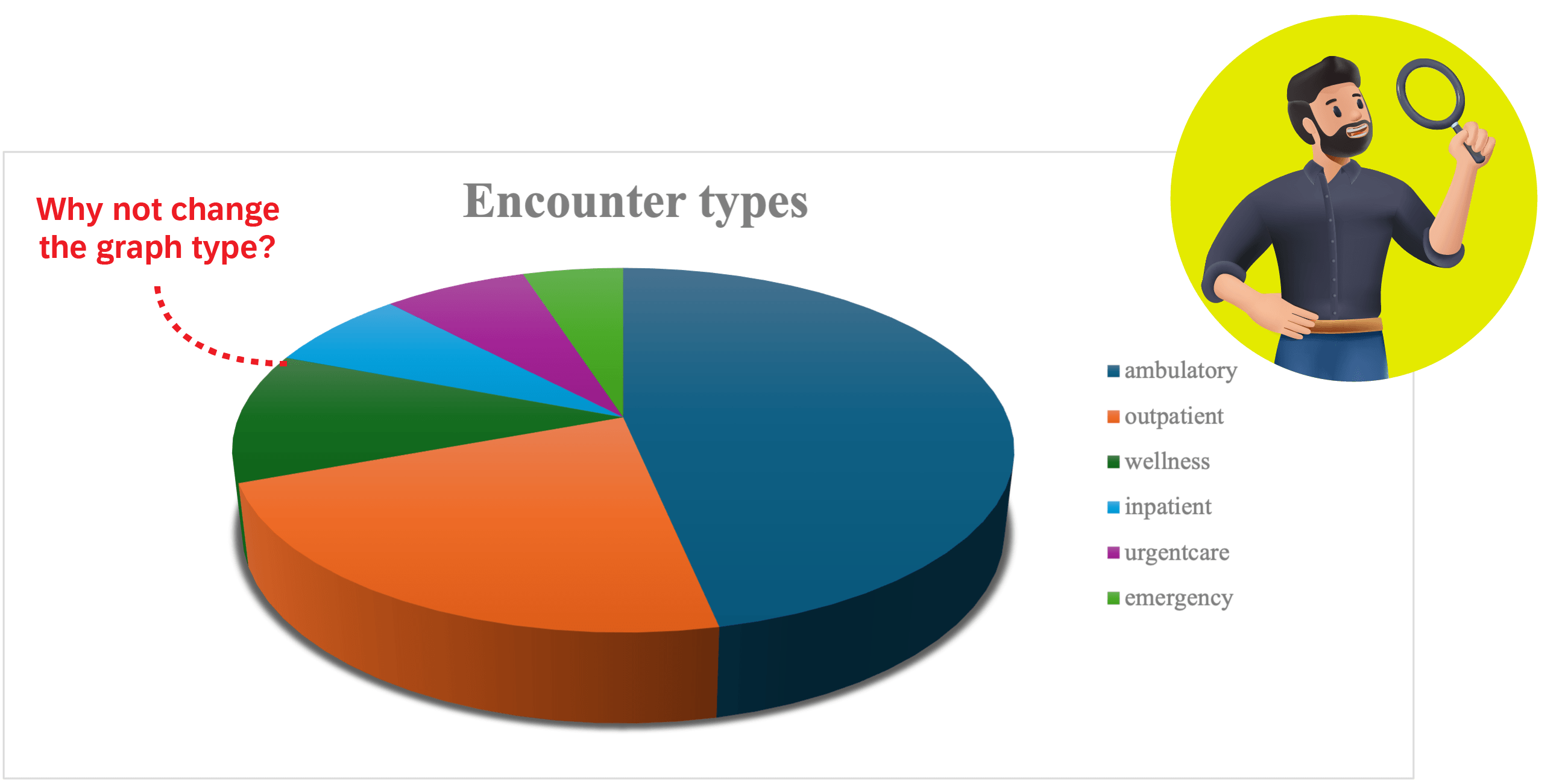

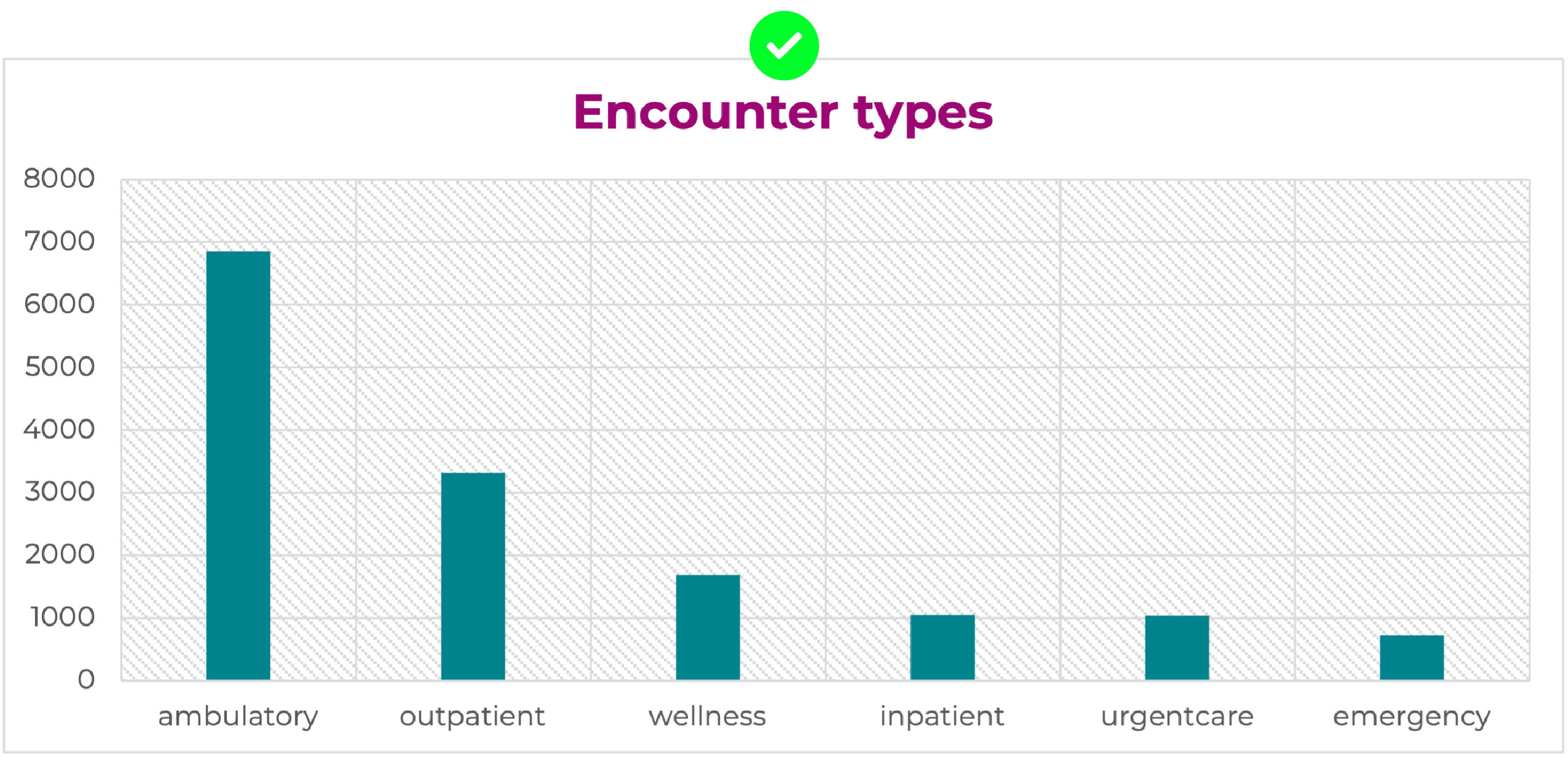

Encounter types

Number of procedures

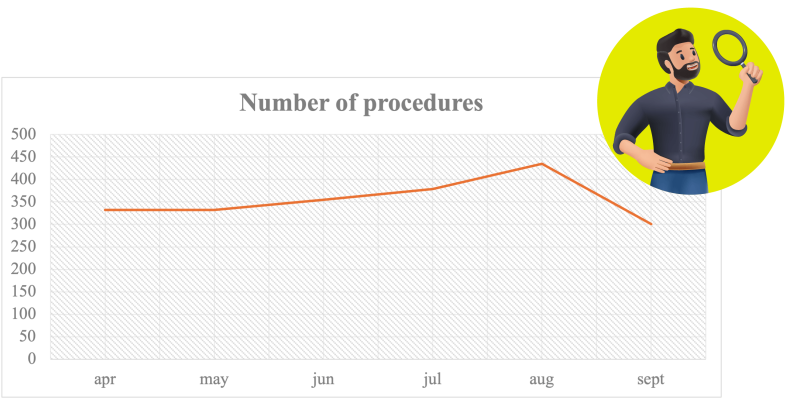

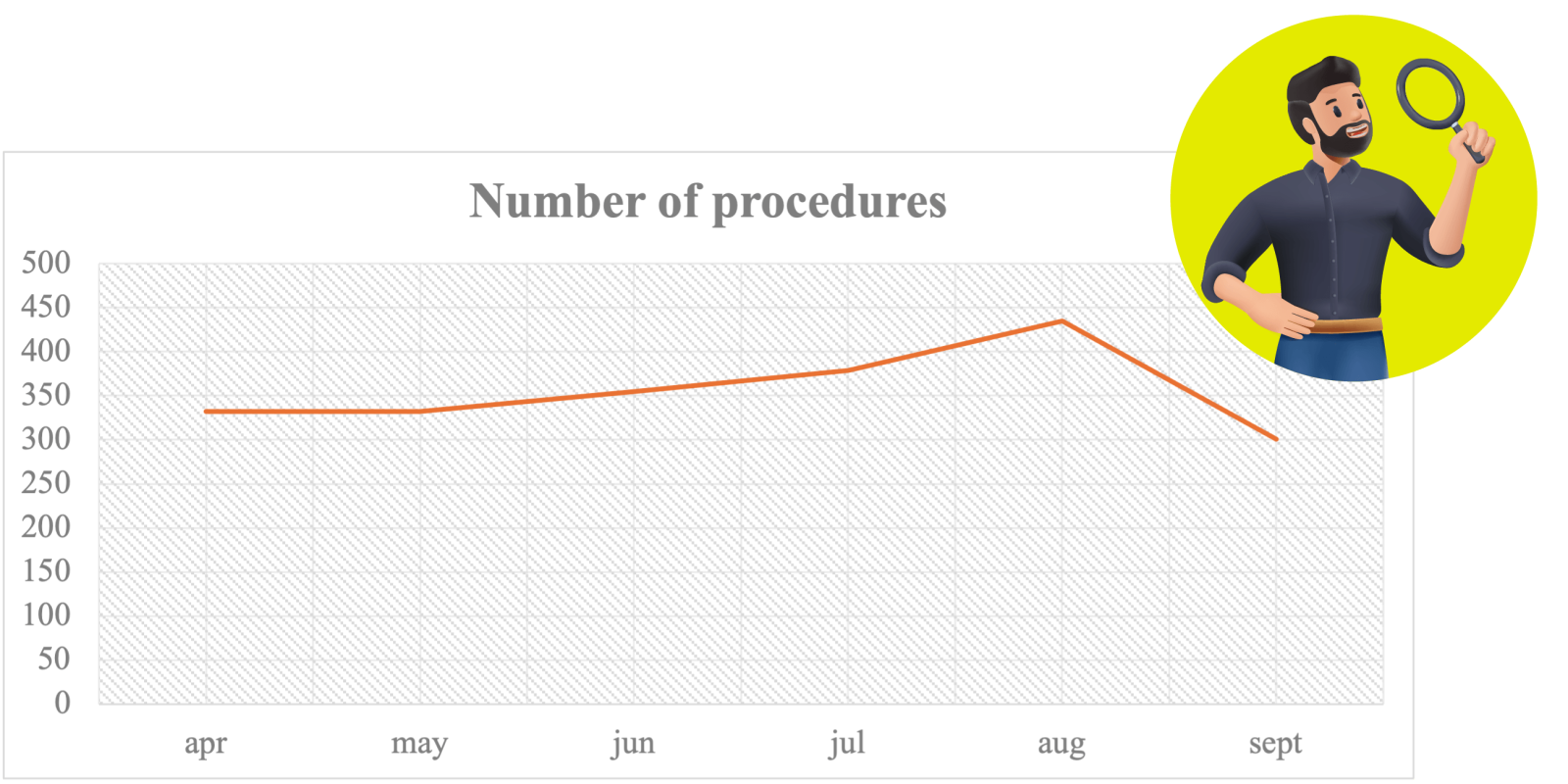

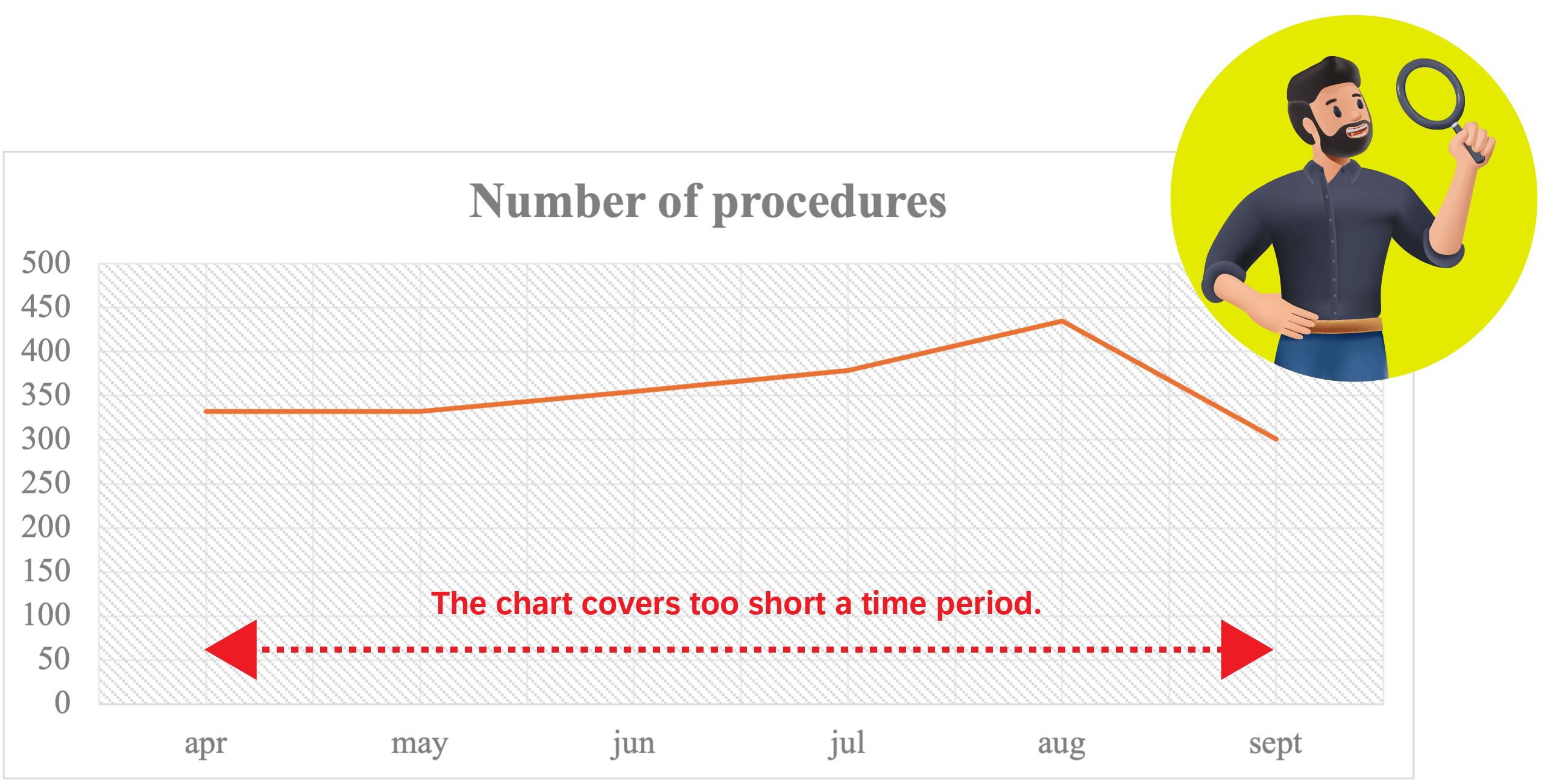

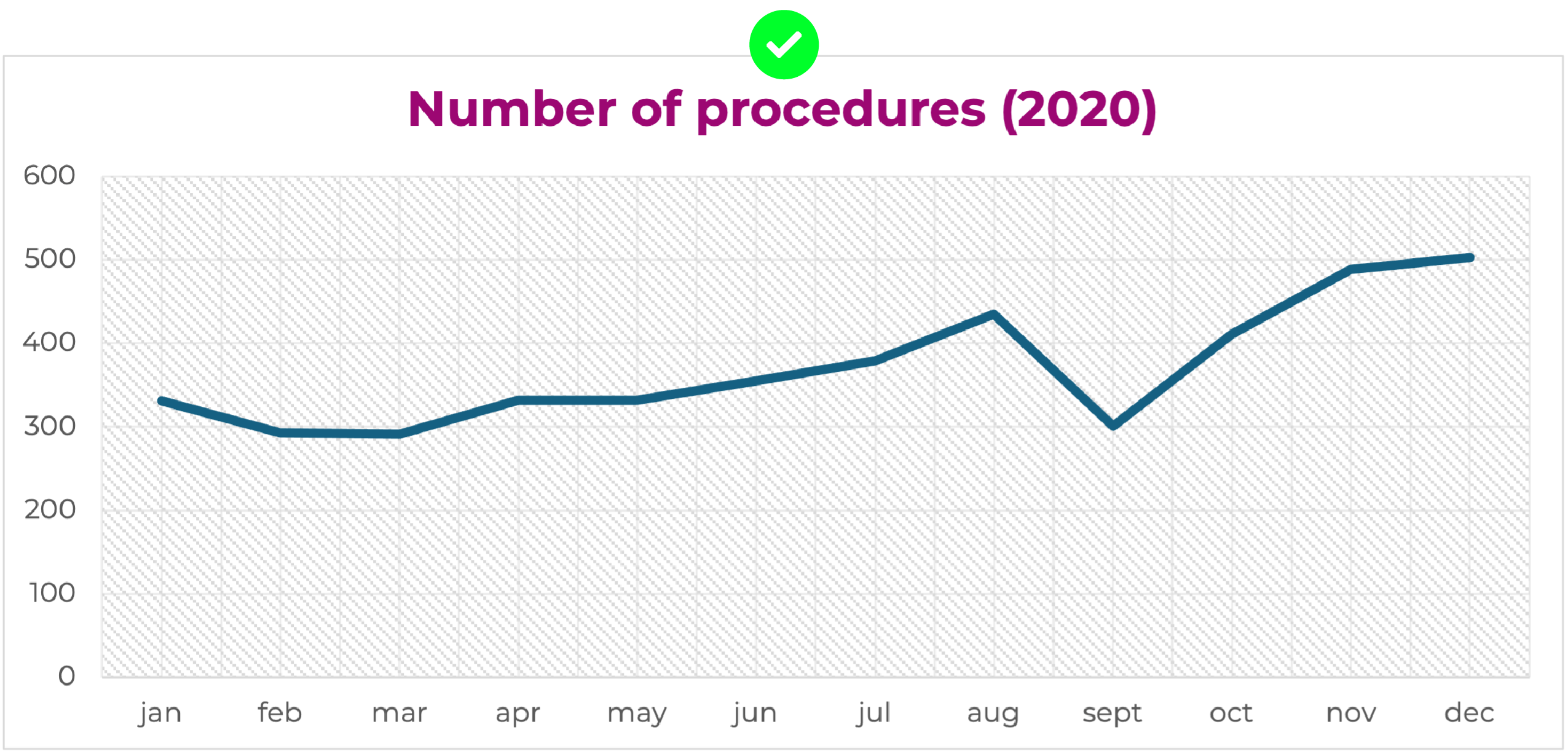

Satisfied with this chart, he then moves to the analysis of the number of procedures the Hospital did in 2020. His supervisor asked him to particularly focus on this year, as the Hospital experienced a decrease in the number of procedures and management wants to know how the trend is changing.

Bob looks at the data for 2020 and then decides to focus on Q2 and Q3, as he believes this highlights the downward tendence that is worth investigating:

Investigating Asthma Trends and Fabrics

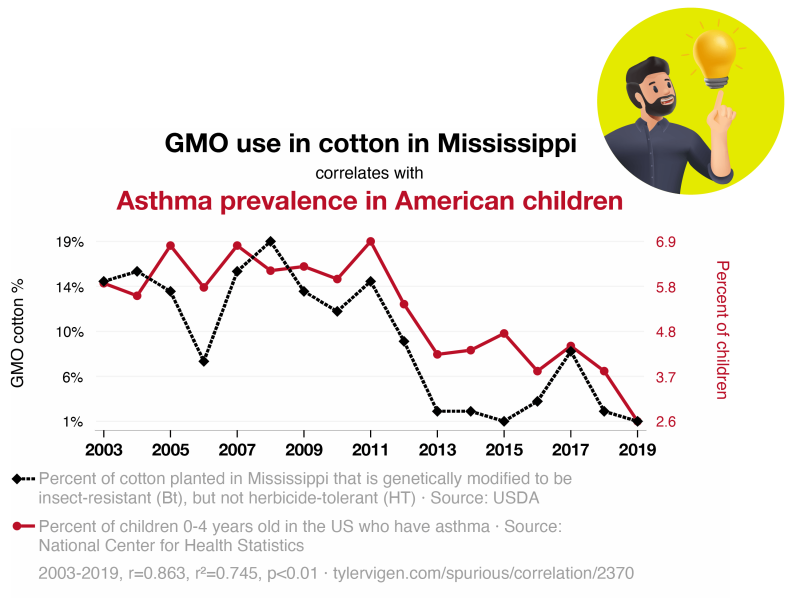

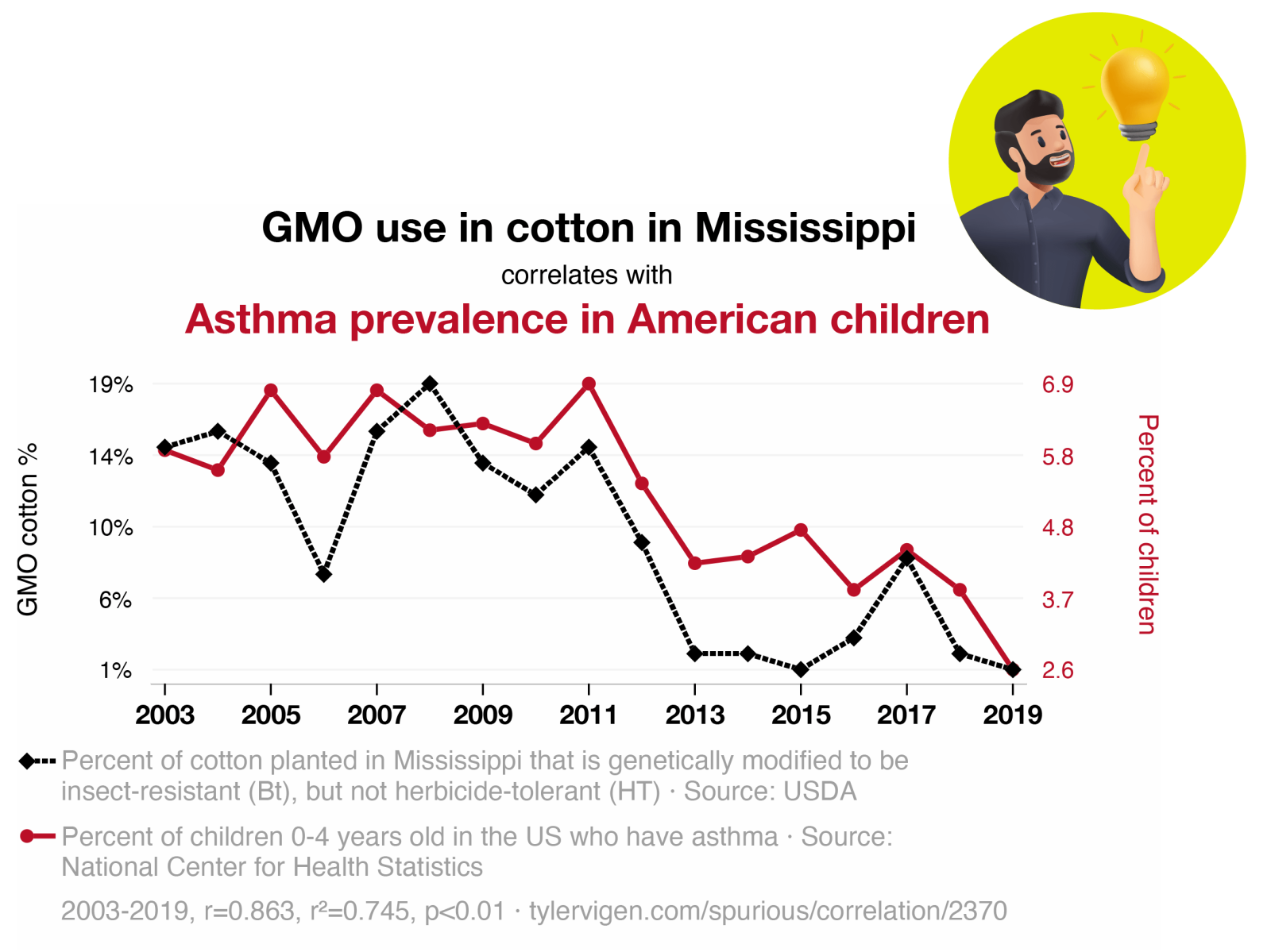

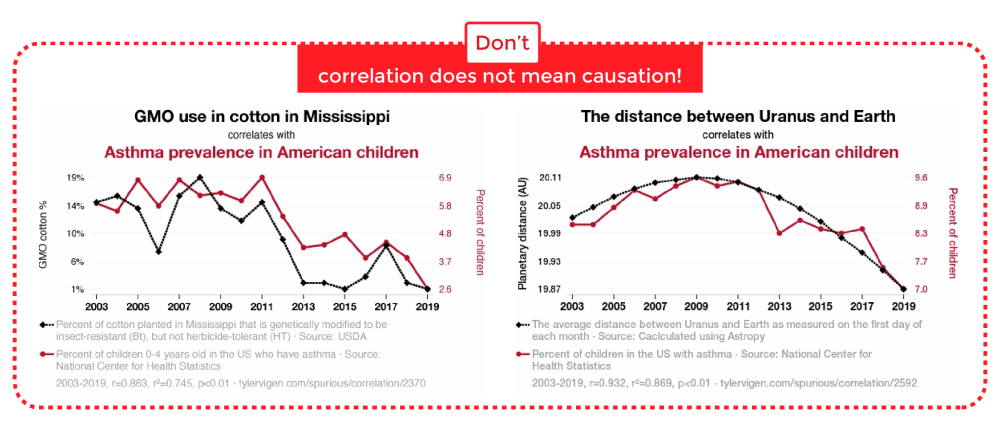

Finally, Bob tackles the topic of the new Asthma Program. He starts looking at data and trends online, deciding to investigate asthma prevalence in US children. Bob thinks that fabrics used in clothes used daily by patients can be connected to Asthma insurgence, and after days of research he finds online data that show how the decline of GMO use in cotton crops in Mississippi is reducing the prevalence of Asthma in children (Chart by Tyler Vigen).

What do you think of Bob’s findings so far?